Sensationalism in Science, Part I

By Gabrielle Rabinowitz

“NASA Discovers Alien Life”

“Doctors Talk to Vegetative Patient Through Brain Scans”

“Sleep Apnea Tied to Increased Cancer Risk”

The world according to popular science headlines is a pretty crazy place. Miraculous cures and surprising causes for all of our ailments can be found in a bite of chocolate. Everything we knew about something is wrong. And NASA has confirmed either the existence of aliens or a world-engulfing black hole.

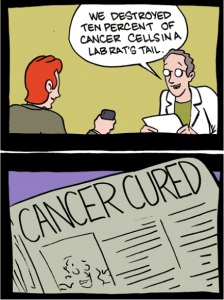

Of course, these are just sensational blurbs intended to grab your attention. Surely the real science can be found after the jump… And yet more often than not, the articles themselves are mere jumbles of over-hyped conclusions, out of context quotes, and clichés. But where do these headlines come from? Buried under all the hype, there is an actual scientific study. This source may not even be cited in the article, but it is out there. It presents evidence for a new discovery, or a new way of thinking about some, often small, aspect of our world. Eventually, the data presented in that study will be reanalyzed, critiqued, revised, and applied to advances in health or technology. But that process is slow, convoluted, and difficult to track. One paper doesn’t single-handedly revolutionize life as we know it, and therefore doesn’t generate clicks, shares, or retweets. So, instead we get hype. More often than not, the carefully reasoned articles only make the rounds as damage control after the hype bubble bursts.

Image credit: Darryl Cunningham

The Harm of Hype

Readers can only see so many “earth-shattering discoveries” debunked before they start to lose their trust in scientific findings. This may explain, in part, why so many people continue to deny the overwhelming scientific consensus on issues like global climate change. It makes people reluctant to trust their doctor. It affects how they vote. And yet, the greatest harm comes not from misguided skepticism, but from misplaced belief. While incorrectly believing that NASA has discovered alien life might result in mild embarrassment, other over-hyped stories have had serious, long ranging effects on public health. One of the most dramatic examples is the panic over the MMR vaccine.

In 1998 Andrew Wakefield (a now discredited surgeon and medical researcher in Britain) published a study in the highly regarded journal The Lancet pointing to evidence that the MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine was associated with autism. This small case study, and a review that followed several years later, triggered a huge avalanche of media coverage, most of it sensationalist and poorly researched. The story spread rapidly, propelled by parents of autistic children who desperately wanted something to blame for their children’s diagnosis. It picked up political overtones and became a vehicle for personal vendettas. The headlines continued for years, each iteration veering farther and farther from the scientific reality. In the meantime, scientists had reached a clear consensus: MMR has absolutely nothing to do with autism.

Ten years after the Wakefield’s first erroneous claims, MMR vaccination rates are only just starting to recover in the UK after a 20% drop. In the US more than 50% of children are not getting vaccinated on time. The repercussions have been severe. Measles was declared endemic in the United Kingdom for the first time in decades. There were still enough unvaccinated children in the UK to generate a huge surge in measles cases in 2011. In 2008 the US reported the most cases in a six month span since 1996. Even a small population of unvaccinated children can destroy the “herd immunity” which protects immuno-compromised individuals, those very few people who cannot receive vaccines safely, from falling ill. In this case, persistent pseudo-scientific media buzz has resurrected a once-vanquished childhood disease.

Image credit: Zach Weiner (SMBC)

Who’s Accountable?

Ben Goldacre is a British writer and crusader against sloppy science journalism. In his 2008 book Goldacre blames “journalists and editors”, but there is more than one weak link in the chain of science communication.

In a paper published in September of 2012 in PLoS Medicine Isabelle Boutron and colleagues analyzed 41 clinical trials with accompanying press releases and news articles. Of this (admittedly limited) sample, more than half of the news articles contained “spin”- defined as emphasis of the beneficial effect of the experimental treatment over limits or risks. Boutron found that 47% of the press releases contained spin and, more shockingly, 40% of the abstracts or conclusions of the papers studied did as well. And as it turned out, the spin in the original source had a huge influence on the tone of the news reports. When not working from a biased abstract, only 17% of the news articles added their own spin. But when spin was present in the original study, 93% of the accompanying press releases had it as well. Spin wasn’t the only thing wrong with these press releases. A full third of them misrepresented the trial’s results and possible benefits of the treatment tested.

NASA published one of the most famously over-hyped press releases in November of 2010. In a few tantalizingly brief sentences they promised “to discuss an astrobiology finding that will impact the search for evidence of extraterrestrial life” in a news conference three days later. Those three days were all it took for the blogosphere to erupt with headlines touting the discovery of aliens. But how can we blame them? “evidence of extraterrestrial life” was right there in the initial announcement. In this case, journalists couldn’t refer to the original paper to qualify their claims because it hadn’t even been published yet.

So, who’s to blame? I hope it’s not too much of a cop out to say everyone: the scientists who first put the spin in their abstracts and then allow press offices to propagate it ahead of the actual paper, the authors of heavily-hyped press releases, and the journalists who don’t look beyond those releases when writing up their own articles. But that’s not all. We’re all accountable as readers, tweeters, and reposters. We all need to read with a critical eye and stop feeding the hype. Not sure how? This list of 6 golden rules for reading science news by Emily Willingham over at Double X Science is a good place to start.

Coming soon:

Sensationalism in Science, Part II where I explore the challenges of communicating enthusiasm for science while avoiding the hype.

Follow Gabrielle on Twitter (@GabrielleRab)

These views are the work of individual authors, do not necessarily represent the views and opinions The Rockefeller University, and are not approved or endorsed by The Rockefeller University.

While researching the invasive Asian clam, I found a high degree of sensationalism in research papers. I fully acknowledge the threat this species poses but, in many instances, the threat has been exaggerated or has been implied based on weak/anecdotal evidence.

I believe this is done in an effort to legitimize the author’s work, which may seem trivial to funding bodies. By highlighting the threat posed to ecosystems and (more importantly)industry the author can place a financial cost on the problem, allowing funding bodies to view their contribution as an investment towards tackling future economic losses.

This species’ invasive characteristics have become distorted to the point that the available literature documents a caricature of the species. When these papers are then referenced by peers, the effect becomes compounded, leading to a widespread acceptance of the inaccurate claims as a determined facts.

I reiterate that I am fully aware of the economic and environmental threat posed by this species and it is a significant threat, but I believe that overstating the problem will lead to accusations that invasive species researchers have cried wolf.

By the time the media get a hold of the research it has already been distorted, though it is often subjected to further manipulation at this point.

I would like to say that the responsibility to prevent the perpetuation of mis-information starts with the researchers, but it is worth remembering that this is a poorly funded area of research and that this research is sorely needed.It can be argued that “crying wolf” gives these researchers the resources they need to tackle what is actually a rabid dog, but it is difficult to decide if the ends justify the means.

Thanks so much for your thoughtful comment. You rightly point out the tension between needing to “hype” our science to get funding while simultaneously trying to avoid misleading our readers/the rest of the scientific community. I think this is a careful balance that every scientist needs to establish for themselves. Obviously, some people are more comfortable with “hyping” themselves than others and it’s unfortunate that we all must deal with the consequences if someone miscalculates. I’m actually going to address some of the beneficial aspects of hype in Part II of this post. I hope you’ll keep reading!