Ebola: A Crisis in Science Literacy

A few weeks ago, an alarming link appeared on my Facebook newsfeed:

“BREAKING NEWS: CDC confirms first case of Ebola in Paramus, NJ.”

Considering that my hometown is only thirty minutes away from Paramus, I was quite shocked and clicked the link, eager to learn more about the circumstances around this confirmed Ebola case.

But instead of an informative article, I was met with this:

Don’t get me wrong, I appreciate a practical joke as much as anyone. But jokes making light of Ebola, as well as shoddy journalistic practices on display in much of the reporting on Ebola, have no place in the fight to quell this outbreak (and don’t get me started on this Halloween costume).

In case you haven’t been paying attention to the news, the worst Ebola outbreak in history is currently raging in West Africa. The Ebola virus is a negative-stranded, membrane-enveloped filovirus– the name is derived from the Latin word filum, inspired by the thread-like shape of this family of viruses- that causes a severe hemorrhagic fever in both humans and non-human primates. This means that upon infection, the Ebola virus enters a cell and lose its envelope. Subsequently, host cell machinery is used to copy its viral RNA into complementary plus-sense mRNA, and then proteins are made. New viruses are then be assembled and go on to infect other cells in the host.

If you’re curious about the details concerning what is known (or not known) about this process and Ebola in general, this wiki provides many references for further reading. If you’re interested in how the human body reacts to Ebola infection (and I don’t mean just a list of symptoms, but the precise reasons behind the symptoms), read this article in Science by Kelly Servick. I also recommend this piece by fellow Weill Cornell graduate student Rob Frawley, to be mirrored on The Incubator later this week. For reading which integrates these elements as well as the stories of researchers, doctors on the field, and patients, this longform piece by Richard Preston is a must-read. Finally, if you’re more of a podcast person, This Week in Virology run by Vincent Racaniello has been focusing on Ebola for many episodes now.

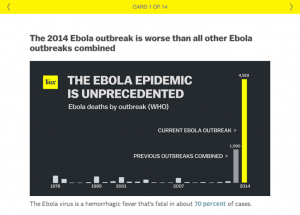

What makes these resources stand out is their commitment to sharing the science behind the news. Many other articles entirely neglect to describe what is unique about Ebola relative to other microbial pathogens. For example, in the Vox ‘card stack’ titled, “13 things you need to know about Ebola,” the first line reads, “The Ebola virus is a hemorrhagic fever that’s fatal in about 70 percent of cases.”

Such phrasing entirely ignores the cause of the fever. While it is true that most readers are probably more interested in the symptoms than the cause, explaining its cause is the only way to properly educate the public about Ebola. Vox founder Ezra Kein has stated that, “Our mission is to create a site that’s as good at explaining the world as it is at reporting on it.” These card-style articles could be a great way to educate readers on the the Ebola virus, one could envision a card depicting the virus, explaining how its genome contains only 7 genes and how its surface glycoproteins bind to certain cell types. Instead, we see a missed opportunity to be ‘good at explaining the world.’

Certainly, news articles should not be expected to delineate every term that is used in an article For example, it would be unreasonable to expect a brief history of the Democratic and Republican parties in every piece of political news. But for topics that are unique, new, or complex, accurate explanations are a must (for example, an article about ISIS should include a brief description of the organization, since ISIS does not have a longstanding history in the public eye). If a deadly virus is deemed newsworthy, then it is the duty of journalists to explain the virus properly, even if this means working through some hard science.

The need for better reporting on Ebola was evident on October 21st in a talk at Weill Cornell from Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Fauci was originally scheduled to be at Weill Cornell in person, but given the more pressing matters he is handling, the talk was conducted over video chat to a packed Uris Auditorium and overflow room. Read more and watch the talk here.

Fauci, who graduated from Cornell’s Medical College in 1966, gave an introduction to Ebola, discussed what is unique about the 2014 outbreak, and laid out ways to better fight the spread of this pathogen. Peppered throughout his detailed, informative talk were comments about the media’s treatment of Ebola. For example, he mentioned that reporters always ask about the mode of transmission for Ebola, questioning if Ebola could somehow morph from direct transmission to airborne transmission. Fauci assured the audience that it is highly unlikely that Ebola would become an airborne pathogen. However, he conceded that when considering biology, anything is possible. Because of this, any reporter can craft a ‘gotcha’ question.

“When you deal in biology, nothing is absolute. There is no 100% guarantee,” said Fauci. “When I try to be honest…some rascal will take that and say, ‘Aha, so we aren’t risk free.’”

Reporters who fish for a shocking soundbyte about Ebola to scare readers in an effort to generate page counts (and thus advertising revenue) are missing the real point in the Ebola story. While it is important to ask questions in order to prepare for the future, reporting has the potential to change culture and policies. Recently, two African children were beaten and called ‘Ebola’ at a school in the Bronx. New Jersey governor Chris Christie has decided to enforce a mandatory quarantine for all healthcare workers returning from West Africa, which is both scientifically and constitutionally questionable. Fear and misinformation about Ebola is causing people in Africa to flee hospitals and not seek treatment for routine illnesses and procedures, creating, in the words of Fauci, a “compounded public health catastrophe”. Of course, we have no way of knowing if more scientific reporting would have prevented such unfortunate situations from occurring, but much of the panic around Ebola in the U.S. might be alleviated if people understood the science of the disease.

While improving scientific reporting should probably become a priority for all news outlets, it has become clear from Fauci and other healthcare professionals that the most important action for anyone to take right now regarding Ebola is to help West Africa. As Fauci said in his talk, West Africa is where the source is, and that’s where the effort should be. I can’t help but think back to the Ice Bucket Challenge for ALS, a viral marketing campaign which raised over $100 million dollars. Now, a virus is causing suffering for an unprecedented number of human beings, and rather than organize a social media campaign to help those in need, citizens of the first world are judging a heroic doctor’s choice of subways and purposely spreading fake news as a joke.

Rather than being afraid or ridiculing those who are actively treating the sick, I’d suggest donating to Doctors Without Borders or one of the many organizations working to end the outbreak. As Fauci grimly explained to a packed audience, “If you have a linear response to an exponential epidemic, exponential will always win.” It’s time to put irrational fears aside and work towards treating Ebola at the source.

Since first drafting this article, both Facebook and Google have created ways for users of their respective sites to easily make donations to organizations helping the fight against Ebola. Mark Zuckerberg personally donated $25 million to the CDC, and now his Facebook users can click on buttons in order to easily donate to either the International Medical Corps, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, and Save the Children. Shortly after Facebook’s decision to make donations possible through their site, Google also launched its own donation program, with the distinction of matching donations 2:1. It will be interesting to see how many donations these methods can garner, relative to the user-generated Ice Bucket Challenge which took the internet by storm just a few months ago. Why has there been no similar public outpouring of support for Ebola? Will imposing a donation button on users actually help the cause? According to ABC News, the American Red Cross has received $3.7 million for Ebola relief; it received $486 million after the Haiti earthquake and more than $88 million in the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan. The public should take Ebola and their ability to help combat it more seriously; hopefully these media donation programs will prove helpful.