A 3 Billion Dollar Mistake: Why the American government should think twice about a Brain Activity Map (BAM)

Update: The United States government has released more information about the specifics of their brain mapping project, now called the BRAIN Initiative. I break down the details and discuss the pros and cons here.

By Gabrielle Rabinowitz, @GabrielleRab

In the 2013 State of the Union address, President Obama praised American scientists for developing drugs, engineering new materials, and “mapping the human brain.” This scientific shout out was not just a pat on the back for American researchers. Rather, it was a veiled reference to a new multi-billion dollar research initiative planned by the Obama administration and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). So what is this plan? As the director of the NIH, Francis S. Collins tweeted:

Obama mentions the #NIH Brain Activity Map in #SOTU

— Francis S. Collins (@NIHDirector) February 13, 2013

The Brain Activity Map (BAM) is a project that will bring together federal agencies, neuroscientists, and private research foundations to create a functional map of every connection in the human brain – numbering in hundreds of trillions. Obama plans to spend $300 million each year on this project over the next 10 years. The researchers and investors involved hope that BAM will drive advances in artificial intelligence, help us understand diseases like Alzheimer’s and schizophrenia, and stimulate the American economy.

Sounds too good to be true, right?

Redundancy and confusion

When I began researching this article, I quickly found bold announcements of an exciting multi-million dollar brain-mapping project, as well as skeptical critiques of the expensive proposition… but they were all from 2011. It became clear that these articles did not refer to the new “Brain Activity Map” proposal, but to an existing multi-million dollar NIH-funded Human Connectome Project launched in 2010.

So what gives?

While Story C. Landis, the director of the NIH’s Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), initially shared my confusion over the announcement, she now acknowledges that the BAM project will piggyback on the existing Human Connectome Project. But what is the human connectome, why is it useful, and what makes the BAM proposal different?

Mapping the brain on many scales, in many animals

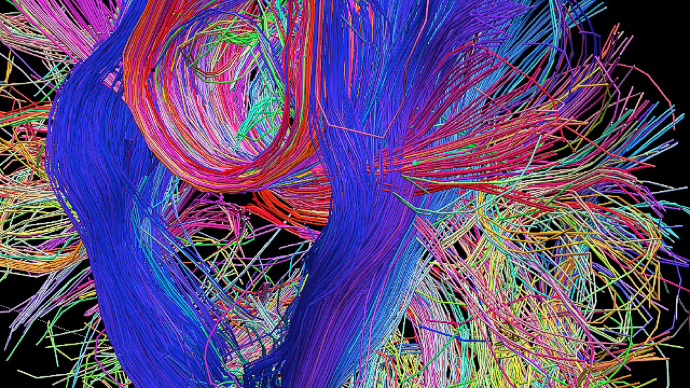

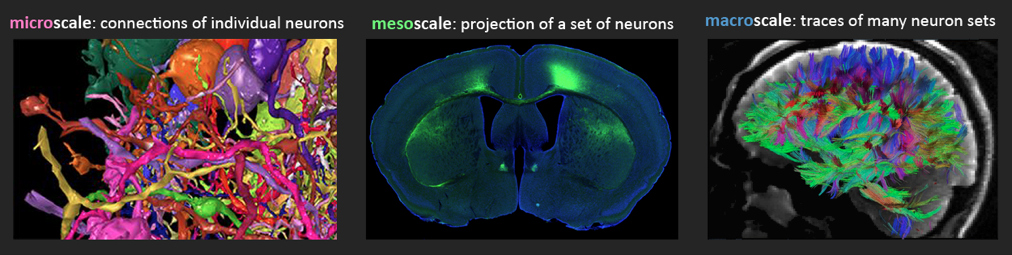

The “connectome” is the complete map of connectivity in a brain- but what does that really mean? There are many types of connections and scientists can look at the connectome on three different levels:

The Microscale: Connections between individual nerve cells (neurons).

The Mesoscale: General area of connection between groups of similar neurons (individual neurons cannot be distinguished).

The Macroscale: Overall distribution of nerve bundles made up of many different kinds of neurons (actual connections are hard to identify).

Scientists are making good progress on the microscale connectome of the nearly 100,000 neurons in the fly brain and others have begun mapping the mouse connectome on both the mesoscale and the microscale.

The only complete microscale connectome was mapped back in 1986: the nervous system of a nematode worm called C. elegans. This worm has a total of 302 neurons, which make only 7,000 connections – far fewer than the trillions in our own brain. So can we predict or simulate a worm’s actions as the BAM proposal suggests we could?

In a word… No.

In spite of the beautiful wiring map, much of the function of the C. elegans nervous system remains a mystery. As Dr. Cori Bargmann, an award winning researcher of these worms and their neurons, tweeted:

@mbeisen Nothing wrong with starting with a connectome — that’s why I went to worms. It poses questions, but doesn’t answer (many of) them.

— Cori Bargmann (@betenoire1) February 7, 2013

One of the biggest problems with “structural connectomes” like the map of the C. elegans nervous system is that they do not account for changes in connectivity. Because neurons are always reacting and adapting, the connectome is not a definitive representation of what is actually happening. It is more of a collection of all possible firing pathways in a brain.

Keeping in mind this caveat, the scientists behind the BAM proposal are hoping to go beyond predicting all possible outcomes. They are working toward showing the actual outcome of neuronal connectivity. But is this really possible?

The Human Brain Activity Map: “Functional Connectome” or Foolish Claim?

The New York Times describes the new BAM project as “a decade-long scientific effort to examine the workings of the human brain and build a comprehensive map of its activity.” The key word here is “activity.” According to the proposed plan, this new brain map will be more than just a connectome. It’s going to be Connectome 2.0: a “dynamical mapping of the ‘functional connectome,’ the patterns and sequences of neuronal firing by all neurons.”

This sounds great. Mapping both the physical connections of neurons and their dynamic activity could drastically improve our understanding of the brain. Unfortunately, there are at least 3 big problems associated with this plan.

Problem 1: Choosing a brain

The authors of the BAM paper write, “For midterm goals (10 years), one could image the entire Drosophila brain (135,000 neurons), the Central Nervous System of the zebrafish (∼1 million neurons), or an entire mouse retina or hippocampus, all under a million neurons.” But Obama and the New York Times have not been heralding the complete mapping of the zebrafish central nervous system.* They’re promising us a human brain activity map. In ten years. Even the extremely ambitious authors of the BAM paper won’t promise that. They say that they “do not exclude the extension of the BAM Project to humans” and will not even try to give a timeframe for such an extension. People expecting a human brain activity map in 10 years are going to be sorely disappointed.

Problem 2: Scale

Remember the Human Connectome Project- the structural connectome on which BAM is supposed to piggyback? That’s a macroscale project. It looks indirectly at mixed bundles of neurons in living human brains. And BAM? Microscale. How will the researchers know from which neurons they’re recording? Will they build up their own microscale connectome from scratch? This is a daunting challenge. Even if they restrict themselves to animal models, the fly microconnectome is still a work in progress.

Problem 3: Technology

Another huge problem for BAM is that the technology to measure every firing of every neurons in the brain doesn’t actually exist. The Neuron paper that inspired the BAM proposal lists a host of “novel methods” (translation- no one’s tried them yet), but does not include any examples of those techniques in practice. Story Landis has said that one of the goals of BAM is to “develop the tools.” Ten years is a very short time to both develop new technologies and apply them.

Flaws in Funding

Back in April, Dr. Cori Bargmann tweeted:

#brainbrawl Ultimate connectome Q is about resources. Fund Seung, Denk, Lichtman? Definite yes – smart, creative. $1B scaleup? Um, vote no.

— Cori Bargmann (@betenoire1) April 3, 2012

She was referring to a different proposal to fund connectome research, but the point still stands. Why would a connectome researcher refuse a billion dollar budget increase? Well, the money has to come from somewhere. In light of recent sequestration threats, it doesn’t seem like the US government is going to be increasing the NIH budget any time soon. If we manage to avoid the fiscal cliff and the budget stays flat, the 3 billion dollars going towards BAM is going to be coming out of the pocket of other scientists.

Dr. Leslie Vosshall, a behavioral neuroscientist at The Rockefeller University, tweeted about the issue last week:

$300 million for Brain Activity Map Project. With flat NIH budget: 750 investigator-initiated RO1s lost per year nyti.ms/XkeczY

— Leslie Vosshall (@pollyp1) February 18, 2013

The R01 is one of the most popular NIH grants for biology researchers in America. By Dr. Vosshall’s estimate, every 300 million dollars that goes to fund a year of BAM would take away funding from 750 American labs. The funneling of government funds into individual massive projects like BAM is a worrisome trend. BAM is not the first massive government research initiative.

Professor Michael Eisen served as an advisor for ENCODE, a recently completed effort to analyze so called “junk DNA” (parts of the human genome that don’t contain genes). Reflecting on the multi-million dollar project in a recent blog post, Dr. Eisen wrote:

American biology research achieved greatness because we encouraged individual scientists to pursue the questions that intrigued them and the NIH, NSF and other agencies gave them the resources to do so.

Dr. Eisen argues that this greatness is threatened by an increasing emphasis on “Big Science” instead of investigator-driven research. In addition to depriving individual labs of funding, Big Science projects like ENCODE or BAM dominate the research landscape for years, establishing a current of trendiness and hype that is hard to swim against. Researchers are often pressured by funding agencies to base their work on the huge data sets that such Big Science projects generate.

The Takeaway: BAM and hype

Here on Behind the Buzz, I keep a lookout for media hype that gets in the way of real science communication. And when it comes to hype, Big Science proponents are often the worst offenders. The increasing sensationalism over the recent BAM announcement is just a taste of what’s to come. And after hype comes inevitable disappointment. The resulting damage to the public trust may be worse than any technological failures or financial costs. Again, we can learn from ENCODE. In recent weeks the scientific community has been in an uproar over an extremely critical paper from Dr. Dan Grauer which trashes the ENCODE project. Proponents and detractors have both turned to hype, derailing the scientific discourse.

To avoid another round of media backlash policy makers need to seriously reconsider the BAM project. This highly speculative, technologically ambitious, and hugely expensive project is the last thing American science needs today.

Follow Gabrielle on Twitter (@GabrielleRab)

Browse the rest of Gabrielle’s articles

*Since I initially wrote this post the New York Times has published a more measured article in which they acknowledge that BAM will not be mapping the human brain any time soon.

These views are the work of individual authors, do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of The Rockefeller University, and are not approved or endorsed by The Rockefeller University.

When I initially read about the BAM proposal I was excited that the administation was sponsoring something that could benefit brain science research. Now that my eyes have been opened to the enormity of the task, and how it could negatively effect other funding, I am much more skeptical. Gabrielle, thank you for digging deeper beyond the enticing sensationalism of science reporting.

Thanks for reading! Hopefully the administration will find a way to support research without throwing money into over-hyped proposals.

Thanks for the awesome post! I really like the tweet integration, too. It proves that substantive scientific discourse can take place in 140 characters or less.

I agree that the hype has got to go. But we need to run a randomized control trial to figure out when Big Science is more efficient than Small Science.

I’ve heard the argument that the Human Genome Project was a good idea because a few well managed sequencing centers could better leverage the fall in DNA sequencing costs than thousands of individual researchers carving out their publishable slice of the human genome pie.

Is the challenge of decoding human brain activity comparable to the challenge of decoding the human genome? The former appears to be much more complicated than the latter. But does that mean we can only tackle complex problems using the Big Science approach? I don’t think so.

That said, investing in new nano brain activity sensors seems like a smart play. Hopefully we keep having this discussion and the proposal evolves towards a consensus.

Thanks for your thoughtful reply, Ethan. I absolutely agree about the power of twitter for real scientific discourse. It’s an amazing way for scientists to communicate directly with the public.

Yes! A meta review of big science results would be valuable, but very hard to conduct without bias.

Collaboration is great, but in this case it’s not simply a matter of sequencing centers. We don’t even have the technology for brain activity mapping yet (at least not on the scale proposed). Investment is one thing, but huge, showy, projects like this are not the smartest way to go about it.

I agree that the best we can hope for is reasoned reconsideration of BAM, and a more modest proposal.

fine by me! as long as the entire process is 100% open.

The reason C Clegans circuit diagram does not translate into dynamics is that 2 things are missing:

(1) the physiological properties of the individual neurons, including transmitter/receptor/ion channel properties, since this sets the dynamics of the nodes of the network,

(2) a model of the rest of the body (and the environment)

Both (1) and (2) could be added to the circuit diagram (which is why it is meaningless to criticize the circuit diagram, like many people have done, as not giving rise to the dynamics – it’s a necessary part of the dynamical model).

This is the “physics” style approach, not “map every action potential of every neuron”. That’s never been the physics approach despite references to “emergent properties”.

I agree. Research into the physiological details of individual neurons and the influence of their environment should be prioritized over massive (and potentially meaningless) recording collection.

Partha,

I want to be careful not to set up a straw man for your argument, but following your logic you seem to be saying (point 1) that no modeling or multiunit recording can be fruitful without a fully specified biophysical model and connection matrix for all the constituents (at least you are say something like that for C elegans). Is that what you mean? Does that mean that you don’t abide any simplified neuron models? No point-conductance Hodgkin-Huxley, no integrate-and-fire, not even multicompartment models without the full complement of channels? Every scientist chooses the level of abstraction that he/she is comfortable with, but your choice would eliminate a huge swath of computational/systems neuroscience. Is that how you mean it?

You also seem to be saying that the ‘physics approach’ requires an absolutely detailed model of nodes and connectivity before anything can be learned. If that is your intent, then I don’t really see that either. I’m not a physicist, but I certainly know some for whom abstraction of network nodes involves a great deal simplification (graph theory, mean field models, percolation theory, self-organized criticality, chaos theory, etc.).

I very much appreciate the care and thoughtfulness put forward in the article above. I resoundingly agree with that we will not have a functional human connectome in 10 years. Moreover, I too agree that the president and the media have blown the promises of the project out of proportion to what will be delivered. Lastly, of course the tools are not there yet. That agreement aside, I think the article fails to consider the effects of the project beyond the mapping of a human connectome. Benefits, I would argue, that would far outweigh the first generation data we may gather from such a map.

Consider the human genome project. When we began the decade-long quest, it originally promised to provide cures to human ailments such as cancer and uncover the key genes that made us human. We have no such answers from that project. Should we thus call that project a failure because the promises were overstated, because it cost billions of dollars to provide us the rough map of one single human being? Of course not. That project helped launch modern day sequencing techniques, fueled R&D efforts and transformed genetics departments, established the promise of personalized medicine (i.e. new business model and emerging industries), and established immense scientific leadership by the United States. We are still reaping the financial and social benefits of that work today. In a flat world, ideas and patents matter more today than ever.

We also went to the moon. All we did was plant a flag. Was that large government project a waste? Think press, think scientific interest, think patents, think industries, think GDP.

What all this means for this mapping project is that we can not simply measure it by its ability to fulfill the promises written in New York Times articles or the estimated 750 grants that will be lost. We are talking about a lot more. For me, from an ROI perspective, it’s hard to argue against.

Thanks for your reply! You are right to point out that big technology initiatives can often drive science forward. However, one difference between the human genome project and BAM is that the HGP had 5 years of discussion amongst scientists and policy makers before it was funded. The technology required was also closer to readiness (see: http://www.genome.gov/12011239). Especially in this economic climate, I find it hard to endorse a poorly defined proposal when so many labs will be struggling to find funding. If the BAM organizers take more time to plan the proposal, there may be a way to fund exciting new neuroscience technologies without launching an over-hyped, over-priced project that is “too big to fail”.

Gabrielle,

Nice thoughtful post. Addressing the problems:

Perhaps there has been a bit of a bait-and-switch on the proposed model organism. I also agree that achieving the goals described by the project in whole human brains is not realistic in the time frame suggested (though I know a few neuroscientists who may volunteer for invasive neurophysiology, no chance of being approved by IRB). Nonetheless, I think the smaller goals are reasonable stepping stones to rodent models, which could give us great insight. Still I agree that the translational medicine pitch is specious.

Scale. I’m not sure (despite your NIH source’s understanding) that BAM can be thought of as building on the Human Connectome project. As you say, the scales not comparable. As for building connectivity models from activity and localizing source cells in recordings, these are non-trivial but definitely tractable problems that systems neuroscientists have been working on for several years. The most fruitful approach would combine structural connectivity information with activity/functional information. In fact this is the approach that many neuroscientists use now, though with fewer cells.

Technology. No the technology to record activity from every neuron in a human brain doesn’t exist and is not likely to exist soon. Nonetheless, the technologies that do exist may be scalable to important and relevant model organisms. There is no way to be sure that throwing money at the problem will produce exponential results, but we at least have the existence proof of the Human Genome Project, where progress has been faster even than Moore’s law would have predicted.

You are definitely correct that funding this proposal in this political climate will be nearly impossible (particularly with sequestration). I also agree that it would be worrisome if this proposal merely sapped resources from existing researchers in other areas. Not being a science economist, I can’t really say whether big/small science is better in general, but I do think that the BAM researchers are right to suggest that the field may be ripe for some coordinated research.

As you know, I’ve also been blogging on this topic, most recently with a recap of a discussion I had with a scientist who helped develop some of the proposed BAM techniques:

http://nucambiguous.wordpress.com/2013/02/24/bam-matters/

Let’s keep the discussion going!

Thanks for taking the time to reply, Michael. You make a good case for a more modest BAM proposal (basically a technology based approach, without the hype). I appreciate the perspective in your post, especially the cited opinions of the BAM scientists themselves.

Great post. And, really, I’m pleased with the conversation taking place about the Brain Activity Map on twitter and elsewhere (i.e. out in the open). Proponents of anonymous peer have often said, without anonymity, we wouldn’t get the peoples honest opinions. I point to this debate (and others) that we can have honest debate, openly and that it benefits us all. While the ENCODE debate has taken an unfortunate turn, I have seen many take the critics to task for being unprofessional. That is a promising development in how we use social media to discuss the future of science.

So, while I can think about many reasons that I don’t like the BAM that’s been proposed, my main critiques are similar to what you’ve highlighted, but they go further. For example, what age organism do we start with? Can you define a normal brain? How do you account for experiential differnces? And so on.

Currently, I am struck by a lack of information from the people advocating for this. And this is what I’m worried about. Some, but not all, of the responses have almost been a dismissive, “Well those people just don’t like/appreciate big science.” Or “The establishment is just happy making incremental progress.” I find those responses inadequate. They have a kernel of truth, but miss the bigger point.

We have a procedure in science to ask people to fund research. Of course it can vary a little, but overall, tell us the problem, how your approach gets at that problem, how you’re going to do it and what it means. If you can’t answer those questions, you haven’t put enough thought into your proposal.

I was struck by this comment in the follow up NYT article “I don’t think this was a major technological innovation,” Dr. Chang said. “But it demonstrates the power of even incremental advances, and shows how they can have a major impact on what we can understand.”

I look forward to the proponents working hard to convince us why this proposal is worthwhile when we have so much work to do already.

Thank you for your thoughtful comment! You are right to point out that there are many more unanswered questions about BAM. I agree that we need to hear some real justification.

It also seems important to point out that Europe just announced funding for a $1.3B Human Brain Project weeks before the State of the Union address:

http://www.popsci.com/science/article/2013-02/how-simulate-human-brain-one-neuron-time-13-billion

I wonder if that was one of the factors that precipitated Obama’s announcement. Fear of getting left behind Europe in brain research? It may also have been pushed by US supporters of the BAM as a sort of independent justification for the validity of the project.

Of course, it’s just as easy to interpret the European project as an indication that the US BAM would be redundant…

I’ve heard some rumors to that effect, and it may well be that competition with the EU was one of the motivating factors for Obama’s decision to fund BAM. After all, Obama promised a surge of technology development “not seen since the height of the space race” and competition was certainly a driving factor then… One key difference between BAM and Blue Brain is that the former seeks to record activity from the brain while the latter aims to simulate it. Of course, a microscale functional connectome would make simulation much easier, but it’s technically not necessary (although a simulation based off of limited data is going to be less accurate).

Hey Gabrielle:

I respectfully disagree with your statement that

>Another huge problem for BAM is that the technology to measure every firing of every neuron in the brain doesn’t actually exist. The Neuron paper that inspired the BAM proposal lists a host of “novel methods” (translation- no one’s tried them yet), but does not include any examples of those techniques in practice.

In fact, that’s a reason very much in favor of doing the BAM. This perspective reflects a belief (which you may disagree with) that brain science right now is largely bottlenecked by the available tools. In addition to theory and to hypothesis-driven research, we do need new types of microscope, broadly interpreted, for looking at the system, in order to enable new questions to be asked.

As Feynman said:

“It is very easy to answer many of these fundamental biological questions: you just look at the thing!” Right now we don’t have the tools to really look properly.

Note that by “look” I mean to stimulate in arbitrary patterns, in addition to passively observing at a functionally-relevant spatio-temporal resolution, and also having the tools to “look” comprehensively during the course of a well-defined hypothesis driven experiment, or alternatively to choose to apply powerful tools to “look” only at a defined subset of the system which you take to be of particular scientific interest with respect to a particular question at a particular time!

To me it doesn’t matter if the right technology doesn’t get fully developed and applied until after the BAM’s stated end date: the fact that a range of ambitious and risky but intelligently-conceived technologies get worked on, in a goal-directed and creatively-brainstormed process, itself constitutes the payoff. Once the technology is there, or even if the idea behind a technology has crossed major hurdles on the way to being there, applying it is ideally much easier and less expensive… that’s the whole point of technology. With the right tools available, we can finally do the science properly.

I offer a bit more of this perspective in a couple of comments on Michael S Carroll’s blog here:

http://nucambiguous.wordpress.com/2013/02/27/bam-and-the-molecular-ticker-tape/#comment-74

Are you against a funding push for a range of efforts in technology development to enable basic neuroscience research?

Best,

Adam

p.s., We’re you at Yale? I was JE ’09.

Thanks for your comment, Adam. My response to your final question hinges on what exactly the “range of efforts” is. If the BAM initiative ends up being broad funding for neuroscience tech development, that would be fine (although if the money is coming out of a flat NIH budget I would still be a little wary of putting it all into one subfield).

My biggest concern is that the money will be given to only a few labs, or will be locked into only a few technologies, which will hinder exploration. I fear that the extra layers of bureaucracy that come along with such a big project might limit scientific flexibility. I wouldn’t want to see researchers forced to pursue an inferior technology, for example, just because it was part of the BAM plan.

The best case scenario seems to be a pool of money available for general technology development… which sounds a lot like the NIH R01 grant program that already exists.

(Yup- BR ’11)

I suppose it’s possible that the project could focus on just a few labs, but we don’t really have that information. If it seems like it’s going that way, I will join with you to call for more broad diverse recipients to preserve competition.

Yes, we definitely have to wait and see what the proposal actually proposes (heh). The way this whole thing has been promoted leads me to suspect that they’ll try to keep it compact and marketable, but I would love to be pleasantly surprised.

>My biggest concern is that the money will be given to only a few labs, or will be locked into only a few technologies, which will hinder exploration. I fear that the extra layers of bureaucracy that come along with such a big project might limit scientific flexibility. I wouldn’t want to see researchers forced to pursue an inferior technology, for example, just because it was part of the BAM plan.

If you listen to this podcast featuring George Church

http://minnesota.publicradio.org/display/web/2013/02/22/daily-circuit-mapping-human-brain

I think you’ll come to the conclusion that what we’ve all just asked for — namely a “flexible” program aimed at “enabling small science” through a wide range of creative and ambitious technology development efforts, “encouraged” by a deeply motivating grand challenge goal — is, in fact, exactly what he’s aiming for, and by extension perhaps what the other scientists who inspired this proposal are aiming for too: “to bloom flowers in many different directions”

Well, cool. I’m very glad to hear those things from Church. I hope his vision holds true. The next question is of course where the money is going to come from with the NIH still reeling from the sequestration.

For real yo

To Michael Carroll: I said no such thing. Obviously one has to keep track of the important variables when making a dynamical model, and not fill up the model with irrelevant degrees of freedom. What is important requires both thought and iterative study.

I’ve spent over a decade studying multichannel neuronal recordings and behavioral recordings and am a big proponent of the empirical (observational) method, as well as increasing the number of measurement channels. There song and dance about measuring many neurons at once and multi-neuronal patterns in spiking activity has indeed been going on for quite some time – it’s hardly news.

However, there is a reason why some theorists have turned to neuroanatomy and are spending time on it. The prior study of many neuron recordings is actually one of the primary reasons that we’ve turned to circuit mapping. This doesn’t mean I (or we) have forgotten about spike trains.

The nervous system is complex and needs to be attacked at multiple levels of measurement and analysis simultaneously – it is a mistake to think all our problems reside in one level of analysis (spike trains of many neurons) and that exclusive technology development efforts focused on that level will solve all our problems.

Exactly why I prefaced my comments the way I did. I’m legitimately trying to understand your position(having read and respected your work from the period you mention). Let me try again.

Your historical point is that many researchers (you among them) who spent the ~90’s trying to record from a lot of neurons have decided that their understanding of the circuits (and individual neural dynamics) was inadequate to constrain models of multicellular interaction/dynamics. Is that fair? You also seem to be saying that no one (at least among those who are reemphasizing circuit mapping) thinks spike trains are unimportant.

Further, it sounds like you feel that BAM proposal is worrisome to you because they have suggesting recording ‘all the spikes from all the neurons’ as a goal. This, you seem to be saying is, not new, and further, some sort of ‘song and dance’ (by which I guess you mean scientifically vacuous, perhaps a way of marketing the proposal). You also seem to be concerned that the BAM approach will only focus on the multiunit spike train level of analysis (at the expense of others).

OK, so if I’ve got that right, then I’ll move on. It’s hard to argue such specifics without more information about what the actual proposal will be, but I think it is fair to be worried about such things (and hopefully influence the discussion during this period when presumably people are still forming the proposal). I have to say, I’m not too worried about the sort of unbound strategy you are talking about. The researchers involved seem reasonably concerned with circuit mapping (Yuste has certainly spent a good deal of effort on understanding inhibitory neocortical circuits). Though not directly involved, we also know (see my blog) that Konrad Kording believes that network dynamics are best modeled on top of a known network because that helps solve the curse-of-dimensionality problem. In fact, if they ever actually allocated the amount of money they are talking about, I would also imagine that you would be on the short list. I’m absolutely not saying that you should be for the project because you might benefit, but rather that with the amount of funding they are talking about (and the model systems they talk about), they can’t possibly fund only a few spike train focused labs.

So, yes. I agree. A large-scale project like this (if you believe in it at all) should be multi-scale and include a huge diversity of approaches. Yes, multi-unit spike trains are best understood in the context of known constituent cell types and connections.

Michael, that is a more reasoned position. I think most neuroscientists will be all for a big push towards studying and understanding brains, the concern is about defining appropriate goals and stepping stones (and keeping in mind the past history).

Of all the levels of analysis the one that has perhaps given me personally the most insight so far, for the integrative working of the whole nervous system, is exhaustive recordings of free behavior. It would not be a far stretch to say that I’ve learned more about how the brain works by studying the song behavior in birds, than from anything else (though this is also a matter of personal scientific trajectory). So I’m enthusiastic about a data driven approach – but across levels, and well thought through.

Isn this programme the same as the HBP (Human Barin Project) which was recently awarded 1.6 Billio Euro by the European Union (http://www.humanbrainproject.eu/fet_flagship_programme.html), within the FET Flagship Programme? Why not to join forces?

There are actually several major differences. The biggest difference is that the goal of the HBP is to create an “in silico” (computer) model of the human brain. They plan to integrate existing models of brain function with an emphasis on “Information and Communications Technologies” (ICT) (an acronym which they amusingly fail to expand on their actual website). A helpful quote from their proposal (http://www.humanbrainproject.eu/files/HBP_flagship.pdf):

“neuroinformatics and brain simulation can collect and integrate our experimental data, identifying and filling gaps in our knowledge, prioritizing and

enormously increasing the value we can extract from future

experiments.”

So the HBP would actually dovetail nicely with BAM, which aims to collect recordings from live brains. HBP could take that data and try to simulate a brain from it… if it weren’t for the other difference:

In spite of its sensational name, the HBP is actually targeting the mouse brain. They are piggybacking off of the work by the Blue Brain group (http://www.humanbrainproject.eu/virtual_brain.html) which is itself an overly-ambitious, highly funded project of questionable scientific merit. BAM, as is becoming increasingly clear, is going to start with the fly brain. So not only do BAM and HBP have different goals, but they are starting with different model organisms.

I realize I’m jumping on this many months after publication, but I only recently came across this article. Very lucid and researched; thanks for putting it out. I would like to point out another concern of Big Science that I don’t often see addressed: The control of an increasing amount of scientific resources (intellectual, not only financial) by a decreasing number of people. Forgetting about the money for a moment, a major move to Big Science means that a small number of scientists get to decide the important directions for neuroscience research. If this were to happen, my fear is that it will become increasingly difficult to publish findings that are not consistent with the big trends. As many other people have noted, good science comes from attacking a problem from many aspects, many spatial scales, and with many theoretical and technological tools. My fear of Big Science is that it will diminish the multi-pronged and multi-lab approach.