Want to keep women in science? Pay postdocs more.

The message is loud, clear, and has reached cultural saturation: women are underrepresented at the top of highly-competitive professions because they cannot reconcile the amount of time needed for such careers with the time they want to spend raising children. Just acknowledging this point has been a recent watershed moment for feminism, triggered by Anne-Marie Slaughter’s controversial Atlantic article and the launch of Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In. Slaughter and Sandberg offer different views on exactly what’s holding women back, but both agree that much of it has to do with raising children. And, of course, each woman and critic has proposed an array of internal and structural changes to help improve work-life balance for women in highly competitive fields.

The message is loud, clear, and has reached cultural saturation: women are underrepresented at the top of highly-competitive professions because they cannot reconcile the amount of time needed for such careers with the time they want to spend raising children. Just acknowledging this point has been a recent watershed moment for feminism, triggered by Anne-Marie Slaughter’s controversial Atlantic article and the launch of Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In. Slaughter and Sandberg offer different views on exactly what’s holding women back, but both agree that much of it has to do with raising children. And, of course, each woman and critic has proposed an array of internal and structural changes to help improve work-life balance for women in highly competitive fields.

Last month, the discussion continued here at The Rockefeller University, where Slaughter presented her thoughts on “The Coming Work-Family Revolution.” Since then, and in light of the larger public debate, young women at Rockefeller have been pondering our own experiences and – let’s be honest – concerns about pursuing a career in academic science.

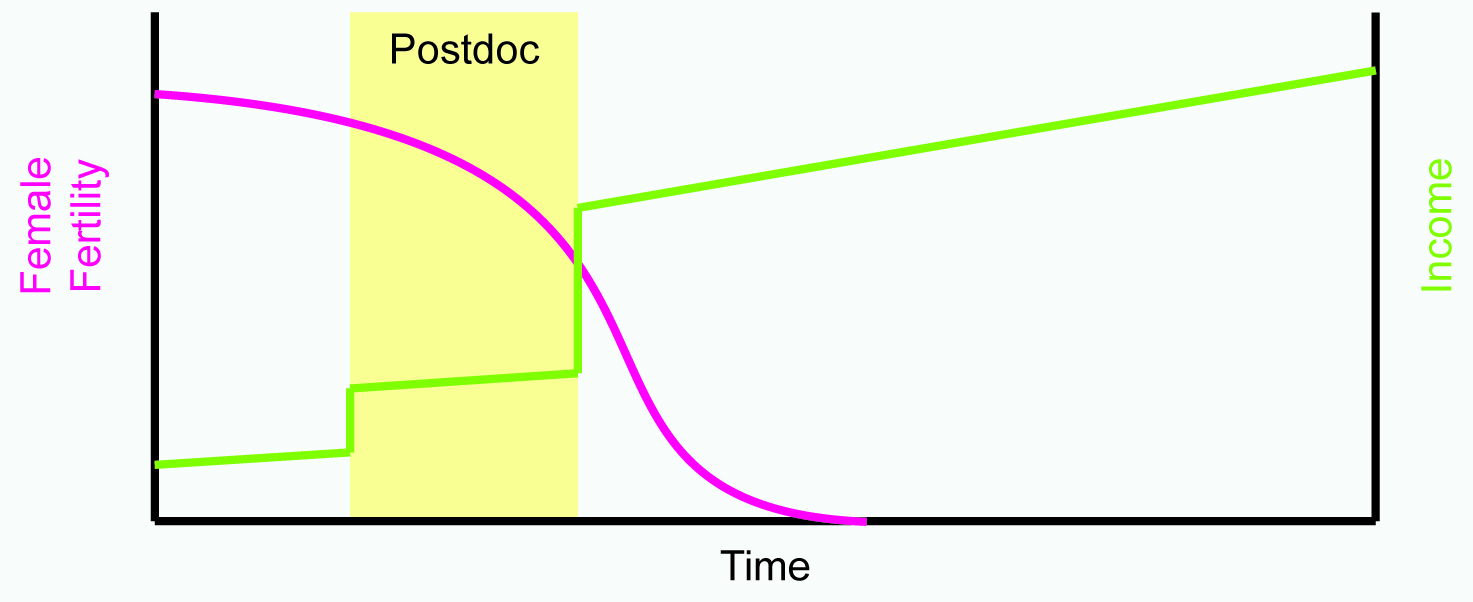

Academic science offers a special case of the more general problem of women’s underrepresentation at the top of highly competitive careers. This is because the problem we face as women in science is actually with one specific career stage: the postdoc. Survey data show that women mostly opt out of academic science just before or during postdoctoral training. Not coincidentally, this is exactly when they have children.

Given that the average age of PhD awardees is 31, women postdocs fall somewhere on the sharply declining portion of the female fertility curve. This is a crucial biological difference between women and men that may partly explain the skew in departures from academic science. Men can put off having children until they land a tenure track job with relatively few reproductive consequences, but if a woman knows she wants to have a family, the wise bet on her own fertility is on having at least the first child before that point, as a postdoc or earlier. Thus, many women postdocs have children, which dramatically increases the odds of their departure from the road to being a PI.

However, the connection between having kids and women leaving science is not simply a matter of long-term work-family time balance. Rather, it is specific to the postdoctoral stage, despite both graduate school and pre-tenured professorship being incredibly demanding. Once women get permanent academic jobs, they leave at a much lower rate, even though their children are presumably still around. This suggests that there is something about being a postdoc in particular that motivates women to leave.

Most postdocs are only paid around $45,000 per year. This is dramatically lower than the compensation of other professionals with similar levels of experience and education. Such low pay leaves women postdocs with much less money than other professional women to pay for childcare and stopgap measures like sending the laundry out. The compensation gap during the postdoc persists for years at the middle of their career, when saving is most important for long-term financial wealth. There is therefore a huge opportunity cost to staying in academic science given the alternatives available to smart, motivated, highly trained postdocs. Adding on the costs of children in both time and money may make other opportunities impossible to turn down.

Women postdocs’ departure speaks for itself. Women leave science to become industry researchers, teachers, consultants, editors, journalists, lawyers, and so on. Many of these professions lack female role models at the top. Most have less flexible hours than science. All of them require hard work. But, again and again, women choose these options over continuing in academic science. We have to ask ourselves why, and the answer is obvious—money. These options all differ from academic science in one key aspect: they are better compensated and more secure at precisely the stage when women opt out.

Of course, many male postdocs also have children. So why don’t they leave at the same rate as women? They soon may. The current makeup of the top ranks of academic science reflects previous generations of scientists. Men’s role in parenting and expectations of fathers are changing so rapidly that the advice Slaughter and Sandberg offer women about making sure to find a partner who will help you balance career and family seems almost quaint. Going forward, the feeling of being torn between career and family may be just as strong for fathers, and the postdoc brain drain may comprise devoted parents of both sexes.

To change the economic calculus for potential scientists, we could pay postdocs more. Imagine that we paid postdocs, say, $75,000/year. This is a modest increase from current rates, but for individual postdocs, and the structure of academic science, it would be transformative. It would allow postdocs to actually afford childcare. They might be able to have a spare bedroom in their apartment for family members to stay in when helping to care for children. They might even be able to put some money away to buy a house or save for their children’s education. These types of changes certainly wouldn’t catapult postdocs into the realm of the rich, but they would make all the difference to a 32-year-old woman who wants children and is considering her next career move.

How could we accomplish this? A major granting agency like the NIH or HHMI could change its salary guidelines, and we could pay for it by having fewer postdocs. Making postdocs more expensive to employ – and having fewer of them – would have the added bonus of decreasing the applicant pool for assistant professorships. The dismal odds of being able to get a faculty job in academic science are certainly not incentivizing women to stay, and weeding people out earlier would decrease the cost sunk into postdoctoral training for those who ultimately don’t get jobs. Of course, we could also remove the postdoc bottleneck entirely by actually increasing overall funding for science to create more highly-paid tenure-track PI positions.

In the end, being an academic scientist, even a tenured professor at a top institution, should not be incompatible with actively raising children. So, let’s do an experiment. See what happens to women’s choices if a large cohort of postdocs can count on being paid a more secure family-friendly wage and not losing out when they spend time with their children. We owe it to the public that ultimately pay for science to make sure the people most likely to make groundbreaking advances become scientists, whether or not they also want children.

About the Author

Jennifer Bussell studies the neural circuitry behind innate behavior as a graduate student at Rockefeller. Before that, she was a biotechnology management consultant at ZS Associates in Boston. Before that, she went to college in Chicago and grew up in South Carolina. She climbs in the Shawanagunk Ridge and still non-ironically enjoys cupcakes. Keep up to date on Twitter @jbschiff.

Jennifer Bussell studies the neural circuitry behind innate behavior as a graduate student at Rockefeller. Before that, she was a biotechnology management consultant at ZS Associates in Boston. Before that, she went to college in Chicago and grew up in South Carolina. She climbs in the Shawanagunk Ridge and still non-ironically enjoys cupcakes. Keep up to date on Twitter @jbschiff.

I like the idea of raising postdoc salaries to relieve pressure on the academic pipeline, and to give early-career scientists (both men and women) one less reason to leave science when they have kids.

Are we willing to go a step further and recommend lowering the number of graduate students in science? If there are less postdoc opportunities b/c we raise salaries, we’re asking for the grad students in science to go do something else. Perhaps they don’t need shiny PhDs in [super unique specialized knowledge within one discipline] for that ‘something else!’

It could still make sense to have the current level of graduate students if it’s recognized that most of them won’t stay in academia, even as postdocs, and they are trained accordingly. PI’s will be extremely resistant to fewer postdocs if we don’t keep lots of grad students around to do the work. That would be okay, though, if their valuable research experience was coupled with career development.

That $45,000 is hugely underpaying when one considers the benefits that are not given to post-docs, who are rarely treated as full employees. Extending health insurance to family is costly. There is rarely subsidy for childcare. These are things that are much more accessible and affordable to tenure-track faculty at many institutions. As dramatic as the wage gap is, it is an underestimate when one considers the lifestyle the money + benefits can buy.

The $45,000 link goes to a chart showing postdoc pay as $39,000. So even the “salaries are way too low” overestimates postdoc pay.

I was trying to be generous 🙂 The NIH minimum for first year postdocs is now $39k, but it does go up in subsequent years. And some people get fellowships. But it’s still insane given postdocs’ education and experience.

Actually, the first year post-doc salary was supposed to increase to $42,000 this year, but because of sequestration and subsequent cuts the NIH had to implement somewhere- they decided that the salary bump was not going to happen. Thus the NIH changed their guidelines and you now find $39,000 back on that site. Of all the places to save money, it is unbelievably terrible that the NIH took money away from post-docs, for EXACTLY the reasons you gave in your article post.

Thankfully, my PI here in NYC is a good boss who values his personnel and wants to pay his people according to their worth. I negotiated for my post-doc salary with him, and worked to my benefit. This was a good lesson that women can and should negotiate for salary, especially if one’s entertaining multiple offers. I also brought up the potential pay cut I would get if I received an NIH postdoc fellowship, and he’s agreed that if I get an NIH F32, he’ll cover the difference of my current salary and the $39,000 the NIH suggests. Again, this came about be just having the conversation.

Even if you were able to negotiate a 50k salary (which is probably much higher than what you negotiated for), it’s still far below to what you’d expect to make after YEARS of education & training. BS/BA holders in other STEM fields start off at that salary level and make far more after 3-4 years.

The problem is not about NEGOTIATION, its about science turning into data manufacturing sweat-shops.

There can also be a significant difference between want granting agencies (like the NIH) say institutions should pay post-docs & graduate students what is actually paid.

Absolutely. Makes one think seriously of the unionization efforts…

It’s not just about income, it’s also about stability of income.

I left academia after my PhD as I didn’t want to be flitting between short-term contracts all over the world whilst trying to raise a family. I wanted security; I wanted a permanent contract. In short, I wanted to know I’d be able to provide for my children before bringing them into the world. Other women may be happier with a greater degree of uncertainty, but I was not, and I don’t think I’m alone.

I am now a healthcare scientist employed within the UK National Health Service. I haven’t left science, and am still research-active.

I wouldn’t weep over women who “leave science to become industry researchers, teachers, consultants, editors, journalists, lawyers, and so on” – these are all challenging careers where their scientific skills will be put to good use. However, if academia wants to retain female talent it needs to take a long hard look at how academic life and family responsibilities fit, and that goes way beyond how much people are paid.

Dr Heather Williams

Director, ScienceGrrl

Heather, thanks for your comment! I completely agree that the huge uncertainty scientists face is a large component of the problem. Paying postdocs more (including meaningful raises each year) would help create more security because each postdoc would be a bigger investment for the PI and postdocs would be less interchangeable and disposable–more like permanent employees in other industries. The initial decision to take on a postdoc would have higher consequences, so there would be fewer postdocs – each worth more to her PI – and each would have less uncertainty about eventually becoming a PI herself given the smaller job applicant pool.

The point was not to bemoan or judge those who choose to leave academia but, exactly as you say, point out to the scientific establishment who *profess* an interest in keeping women in science how they might do that.

There is clearly more in play than just how much postdocs are paid, but those issues (albeit large) are more similar to other highly competitive careers. I am arguing that science is unique in the structure of career progression and this in particular is a huge barrier for involved parents, which, in the past, have been women.

Thanks for mentioning that men are increasingly being affected by the level of postdoc pay. Yes, some men care about their families too.

I’m a male, I love science, and I have a wife and two kids. We’re not from independently wealthy families, unlike some trainees/scientists I’ve met, and therefore need to cut corners to make ends meet.

But I’m increasingly thinking of quitting academic research for the sole reason of the pay levels, but not only for the sake of my family; Even when I “make it” and pass through the PDF stage, I’ll still have to hire trainees at embarrassing levels of compensation.

I’d rather hire the best people to work for me and keep them happy. If I can’t do that in science, I’ll have to do it somewhere else.

There does seem to be a generational difference in how much work-family balance is considered a “women’s issue.” We’ve made so much progress towards men being equal partners in raising children that it seems to me, at least, that your feelings are the norm, certainly among young scientists.

I love your point about wanting to pay your own potential trainees well. I’d love to see what would happen to a research institution or even lab that offered appropriate compensation to trainees. I think this is part of what HHMI’s Janelia Farm is trying to do, although their focus seems to be more on taking funding pressure off of PIs.

Higher salaries would be great, however, blaming the children is to take the easy way out. I have children myself and know everything about the constant juggling, it isn’t easy but I don’t think that is really problem. In Sweden we have had affordable and good, public day-care since 1975 (almost 40 years!). Our numbers of women in higher positions in academia are as poor as the rest of the world. Other issues are equally or more important. I expand this more in my comment to Nature geoscience in 2011 http://www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/v4/n6/full/ngeo1163.html.

Stop blaming the children and focus on the real problems, who do we choose to promote? who is getting access to high power networks? who is invited to the high-profile club? who is regarded as excellent? (yes, it is a matter of opinion with a snowball effect). We can change the system, the question is if we want to.

I’m certainly not blaming the children but rather the system that makes having children a huge impediment to keeping up with childless peers. In the US, affordable good daycare is basically unheard of, so the problem is quite different.

The evidence for my argument that the balance between children and work is a major cause of women leaving science is the timing of women’s departure. There is a strong correlation between women having children and leaving. For your hypothesis that the *primary* problem is discrimination to be true, women would have to be underrepresented at *all* stages of the scientific career and “considered excellent” less than their presence at that career stage. That does not seem to be the case.

I’m not sure listing journalism as an alternate career choice is a good example for your point. For science journalism at least, no one goes into that profession for the money. $45K is actually considered a reasonable salary for a beginning journalist. The job may potentially offer more schedule flexibility for freelance journalists, but it’s a hard industry to get established in.

Except that science journalists leaving science are competing with folks without advanced degrees and potentially less work experience, so an entry-level salary makes more sense. There is also a large potential upside for journalists who make it, and for non-freelance journalists, the job is different from a postdoc because it has benefits and no set cutoff where one is likely to have to leave the industry.

No one goes into science for the money, either. My point is not that we should reward people looking to get rich. Or that scientists shouldn’t be devoted to research. My point is that it’s shortsighted to weed potential scientists out based on who’s willing to put up with the most insecurity and least amount of money.

Another item that would help, is access to onsite, subsidized day care.

When I was a postdoc at Harvard Medical School, the New Research Building had a potential area on the ground floor that could have been used to house day care. Instead they used this space to build a gym.

I have to tell you, “this ain’t gonna work.” Unfortunately, I can’t tell you what will, but I as a female PI, I can tell you this will not. In fact, I think it will make the situation worse.

First some background. I am a 40 year old PI, Associate Professor running my own research laboratory. I was an Assistant Professor at 31, first baby at 34, first R01 at 35, second baby at 36, tenure by 38. I currently earn just over six figures. I had great supportive mentors, I worked hard, but a lot was luck. I don’t think this can be done now. It was pretty damn lucky 10 years ago. Oh, and my husband and I managed a dual hire in the same department. Which of course is the other major thing that holds women back – the two-career problem.

And I almost didn’t even interview for that first position because I thought academic science was too competitive. I hate to gender stereotype, but I really think that the average woman is naturally more risk averse then the average men. Money is not the problem – women want stability. If you force everyone to pay post-docs 75K, post-doc positions will shrink dramatically. I am guessing 50-75%. Why would I pay someone 3/4 of my salary when they only have 5-6 years experience, most likely not directly in my field? I can pay my experienced technician half that and she already knows how to do all the assays in my lab. Grants are so hard to get right now and PI’s need to conserve the cash they manage to bring in. Unless you are running a super successful lab, you will simply not be able to afford a post-doc. It is simple economics. I predict that the raising of salaries will lower the number of post-doc positions dramatically causing greatly increased competition that will drive more women away than men. Net result – less women in science.

I wish I could be more positive and offer an innovative solution, but the land of academic science is not good right now. Women who are getting out may be making the smarter decision.

First of all, I emphatically disagree with your characterization of women as more risk averse, particularly given the past trend of women’s greater responsibility for raising children, which–as I pointed out–is now rapidly changing. Perhaps, at best, PARENTS are more risk averse. And the highly competitive nature of science is not unique—that’s true of all the fields Anne-Marie Slaughter and Sheryl Sandberg discuss. But only science is that competitive AND this underpaid. In fixing the underpaid part, we can also make it a little less competitive and competitive in a better way.

It is helpful to neither science nor science PhDs to maintain a large number of poorly-paid postdoc positions with the promise of eventually becoming a PI. I get why PIs want to do it—they get a large pool of experienced cheap labor. But only people willing to put up with the low pay stick it out as postdocs, and that’s a really bad way to select who eventually gets their own lab. You can tell it’s not working by the fact that women are so dramatically underrepresented in PI positions.

Both you and other PI commenters bemoan the large decrease in postdoc numbers that will happen if they are paid more, but that decrease is part of the solution. Postdocs are not interchangeable assay robots doing science for PIs. They are scientists developing their own research programs before moving to their own labs. If you need someone to run assays in your lab for “productivity,” hire a technician or staff research scientist. If you want to mentor someone on the way to starting their own lab, it’s going to cost you, but you will get an intellectual ally to think about and contribute to your lab’s science.

I don’t want to quibble about the actual salary number. It seems we can all agree that the current one is too low and postdocs probably shouldn’t be paid as much as PIs. But it seems to me that there could be a happy medium where we could still offer opportunities for scientists to work on a second project after their PhD before starting their own lab but we wouldn’t pay them so little that people with children could’t afford to do it.

It’s true that many, many scientists would have to find other careers if there were half as many postdoc positions available. But even more of them have to find new careers anyway when they don’t get jobs *after* being underpaid for five years as a postdoc. How is that better? We need to do a better job mentoring and preparing graduate students so that we can identify and encourage those with the potential to stay in science and appropriately train those who will leave, rather than leaving this sorting job to the crappy pay and insecurity encountered as a postdoc.

I’m afraid I have to agree with Anonymous PI. Among all the friends and acquaintances of mine who have attended and/or finished grad school in ecology-evolutionary biology (EEB), I know of three who went on to enroll in veterinarian schools after obtaining PhD (or dropping out of grad school). All three of those are women, and at least one of them told me that she didn’t really bother to tackle the dismal EEB academic job market in the first place.

While I realize that my example is anecdote, I don’t think the notion that women are naturally more risk averse is unfounded stereotyping. Rather, it’s simply a phenomenon that we need to acknowledge and address. The main reason for the high drop-out rate for women from science is the ridiculously high competitiveness in science. And the only way of mitigating that is to decrease competition by increased opportunities, both at the postdoc and faculty levels.

I agree with anonymous in that increased average postdoc salary will likely further decrease postdoc opportunities (which is already scarce as is for EEB), therefore exacerbating the competition in academia. Instead of fighting for a moderate pay raises during one stage of our academic career, I think it’d be more fruitful to find ways of boosting our job security overall, which would be more conducive to retaining female scientists.

You’re right, clearly we must protect the delicate weak ladies who can’t handle competition. This type blatant stereotyping, bias, and patronizing are not holding women back at all.

Look, women represent over half of the students at the most competitive colleges. They’re also half of the graduate students–do you really think the primary issue is that we’re not willing to compete?

Show me the evidence other than your three acquaintances that there is a real biological difference in women’s risk aversion that is not caused by being a primary caregiver for children.

Until then, I maintain that the introduction of children into the equation is the problem. ANY parent spending substantial time with his children will face the difficult tradeoff and need more incentive to stay in science. This has more often been women in the past. It affects men also and perhaps makes active PARENTS more risk averse. NOT JUST WOMEN.

OK, first of all, science is about understanding facts and phenomenons rather than emotions and politically correctness. So as scientists, let’s try to be logical and less emotional, even when discussing issues that personally affect ourselves.

In the Nature article you linked, they stated that it’s the “meeting the demanding schedule of academic research” that’s impeding young scientists who are or would be parents. In other words, even assuming having babies is a major factor, the real reason is the time demand rather than low pay. If it were purely financial, then the situation should impact male and female postdocs equally, unless you tell me that daddy PhD’s are also financially less responsible for babies (in addition to disparate time investments).

And I think you are also confounding arduousness with competitiveness. Grad schools are no doubt very demanding, but the competitiveness of entering grad schools is child’s play compared to the competitiveness of landing TT academic jobs. It’s this ridiculous competitiveness that’s driving out many women (and men) from a science career IMO. And the way to mitigate this is by allowing more young scientists access to funding and employment opportunities, NOT by allocating more $$ to even fewer “elites”.

And lastly, I’m not trying to be patronizing. As an unemployed (male) PhD, I’m the last one qualified to patronize anyone right now. My PhD advisor is a woman, and I’d like to see more women in science. I just think we should correctly identify the causes and devise appropriate solutions. BTW, all three women in my previous example are childless, with two of them actually still single. So children is definitely not the reason in their cases. In fact, I also have several female friends with kids, who have successful academic careers. Sometimes it actually appears easier to succeed in academia for people with families. They can have access to certain privileges such as spousal hire, but that’s a whole other discussion.

Calling out via sarcasm the sexism in your assertion and how it contributes to the problem is not being emotional or politically correct. You calling it “emotional,” however, as well as the rest of your first paragraph response continues to be sexist and patronizing.

To reiterate, my argument is that women leave science for other careers that also place large time demands on parents because having more money helps parents cope with the time demands, and science doesn’t allow that.

The situation *does* now impact male and female postdocs equally, in the cases where male and female postdocs spend equal time devoted to their children, which are becoming the norm. The current representation levels reflect conditions in the past, so today’s dynamics will play out in the relative representation of parents/men/women at the top levels of science in the future.

Having additional $45k/year temporary positions for people who are not likely to succeed at continuing in science is not going to create more “funding and employment opportunities” for young people to have long-term careers in science.

Finally, college entrance, for example, has become remarkably more competitive recently (not arduous).

Would you give a difference of $15k per postdoc per year? That would be a very competitive wage that would raise a lot of attention and competition for people to work in your lab. Given you may have a budget of 1-2 million dollars for a few years if you’re doing ok, thats about a ding of 1% per postdoc. So if you have 2 or 3 postdocs, you may have a much more financially secure and lower-stress workforce with a deduction of about 2-3% of your budget. To me, that’s an analysis each PI should consider. To beat this problem, the people who made it out of the problem ought to look back to others with sympathy — its shameful, in my opinion, that you’ve struggled and would rather buy more experiments than to alleviate the same struggles from your own workforce. There is a saying in parenthood where we strive to provide a better life for our kids than we were afforded. Mentorship can have similar facets if you choose to care enough.

You make an interesting case, Jennifer. Raising postdoc salaries seems on the surface to be the right thing to do.

But the current funding process makes this hard to implement. The salary level you suggest, $75k, would cost PIs between $140k and $150k per year, because you have to add ~23% benefits and 50–60% indirect costs. That is, the university would take a cut of $55k per year to house that postdoc. That’s $165k in 3 years just in F&A costs.

One has to consider also that reducing the number of postdocs overall will hit productivity of the science enterprise. A small lab may employ 4 grad students and one postdoc; a large lab may employ 10 grad students and 3 postdocs. Either one will see their productivity cut in half without the postdocs (thumb-waving estimate). This sounds like another argument for increasing postdoc salary … they play a vital role in the productivity of research labs. But we’d need the cooperation of the university’s office of sponsored research by setting lower F&A rates on salary.

Not happening anytime soon. The NIH Working Group on the biomedical research workforce headed by Princeton president Shirley Tilghman encountered serious opposition when they tried to raise postdoc minimum wage from 39 to 42k… and now you want this doubled?

Just gotta face the reality that we are in an era of outsourced science. The smart ones already see the trend and moved on. Dont be the one left holding the bag.

And have more permanent positions after postdocs! Could be research scientists at universities or national labs, with long-term (multi-year) contracts, or multi-year contract teaching faculty (lecturers), in addition to the classic tenure-line prof positions. There are ever fewer of the latter, and the other post-postdoc options offer almost no job security and often no benefits. Women take one look at that and head for the hills. If there were more paths for career advancement that offered some stability for women (and men! and their families!) and decent pay/benefits while staying in science research and teaching, more women (and men!) would stay in the field. It does not just have to be tenure-track professorships – the other options could be attractive, but only if they have multi-year contracts, decent pay, and benefits! It’s all the one-year, no-benefits, low-pay contracts that chase women (and men!) out of science. If we value scientists, then we need to put our money and our structural positions and career tracks in academia and research where our mouths are. Note that $75K is almost certainly an unattainable goal for a postdoc salary, given that starting tenure-line professors make $65K at many universities, and that lecturers and staff scientists with several postdocs under their belts are lucky to make $45-$55K for a 12-month salary. Let’s talk about the stability and the restructuring of academic science to make more types of long-term career paths with job stability and benefits outside of the tenured professorate – that’s something we might be able to manage, along with paying postdocs more along the $45K line (which is about average in my field, astrophysics, so rather better than biology it seems).

One thing the NIH could do is provide more supplemental money for NRSA fellows. The current level is $7,5000. For individual insurance at my institution is $4,000. Providing/purchasing family insurance would cost me $10,000. This was a huge, tremendous stress on me and my family, never mind that attending meetings and buying a piece of equipment was part of the training plan. My husband and I took a gamble by not providing him insurance under me and we lost big. The stress of the situation when he got sick caused me to have to take some time off to deal with the financial implications for our current and future life.

I know 3 females at my institution who are the main providers, whether their husbands don’t have work visas, are finishing school, or are simply the stay at home dad. These 3 females won’t apply for a F32 or K for that matter because of the implications of the health insurance.

I don’t understand how increasing postdoc pay would increase a female’s desire to “stay in science.” Of course it appears that the only definition of “science” here is tenured track professor at an academic institution. Sorry, but science can actually occur outside the hallowed halls of academia. But that is a different rant. So is the idea that you must have a phd to do science. But that is also a different rant.

So let’s change this to the argument of “paying postdocs more would encourage more women to get a phd and stay in academia.”

1. When did postdocs become a greater than 3-4 year job? Back in my day (and I am only 32) postdocs positions were for cranking out papers, getting independence,getting some grant funding, and/or obtaining new training….and then moving on. But I see more and more career postdocs. Yes, the job market is hard. But it is hard all around. It shouldn’t take you 7 years to qualify for a job. I mean, I know men and women that I went to graduate school with that are still doing postdocs and I have had 3 jobs since then. (In industry…which is still science). Although most of them seem happy where they are so guess it works for them.

2. If you are aggressive in your programs from undergrad on up, it is possible to get your PhD when you are 26-27 (I finished when 27), a post doc under your belt by 30-33 (I finished mine by 29), and start your science career by 31-34 (got my first -nonacademic but totally awesome science-job at 29). Which if you want children (don’t assume all women want children because I am a woman and I don’t), that gives you time to get to a job that affords $ for childcare within the proposed “breeding years.”

3. And you can also find a science job outside of academia at a good company that appreciates the need to have a flexible schedule for family time. All of my jobs have understood when someone left for an hour to go to a recital or needed to work from home when life gets in the way.

All that said….I think that funding should increase as cost of living increases and that it should be adjusted based on the cost of living for the region ($45K in Texas vs $45K in Boston is a big difference). And I agree with Rebe that maybe there is a different type of academic position after postdoc that isn’t tenure track professor that allows women to stay in academic science until a tenured position occurs.

Completely agree!

First, it’s clear that throughout the piece I’m discussing academic science in particular even though there are many “science” careers outside of academia because it is at the top ranks of academic science that women are so dramatically underrepresented.

Second, I’m not saying that increasing postdoc pay would increase desire to stay in science. It would decrease the cost of staying in science for parents who already want to have children and stay in academia.

Postdocs became this long because there is an oversupply of postdocs relative to tenure track job openings and postdocs are cheap highly-trained labor.

Yes, it’s possible to move very quickly through the career track and be at the assistant professor stage younger, but that’s not the norm and shouldn’t be a prerequisite.

I feel that I am basically the model for this article. I am female, 32, the primary breadwinner in my household, had one child whilst a PhD candidate, and left my academic post-doc after 8 months for an industry position. My salary jumped from 39,000 USD/yr to 95,000 USD/yr, which offered my family significantly more security and the option to have more children. Until post-docs are paid what they are worth, women (and men) will continue to take the smarter option and opt-out of academic jobs where they are undervalued.

The title is misleading and sexist… Why should women be the only ones in charge of raising children and not the men? I think that the problem will be solved when raising children will be become equally important to men and women. Also agree to increase post-doctoral salaries mainly because of the job instability, independently of the gender.

Read the post. In no way do I imply or support the notion that women be more involved with children than men.

I recently completed my Ph.D. and decided not to stay in academia. The pay was only part of the problem in not pursuing a postdoc. Performing my doctorate at a major medical center in Manhattan I saw postdocs abused, verbally and emotionally. I also saw that the only postdocs starting families had spouses who were in finance or, after completing their PhD’s, went into Law or Patent Paw, etc.

Adding to that was the lack of role models in PI’s I saw in my institution. I think that out of more than 200 professors who ran labs, only a handful actually had a healthy and functional family life.

Especially in the days of people performing more than one postdoc, lasting well into their mid to late 30’s, to obtain a high ranking faculty position, the pay must increase to keep the smartest people in academia. But I doubt that PI’s will be happy to pay an individual postdoc more and have fewer of them.

I think of the Confederacy and its unwillingness to give up their relatively cheap labor force when people talk about postdocs. It will certainly be a fight to change the status quo.

Although this article highlights some interesting points, the analysis is too narrow and obviously biased by the professional characteristics of the person who wrote it. The same analysis should be carried out by a woman who had gone through the different phases of the academic career, and hence can see the whole picture, because obviously a postdoc does not have the personal knowledge to analyze what happens later.

I do agree in general with the fact that salaries in the academic profession should be higher. However, I do question at which stage the increase has to take place. Postdocs in Europe are actually paid at a much lower rate than in the USA (and the cost of living is not necessarily any lower). However for the stage of the career they are at, the salaries are very competitive when compared to what it is offered in industry. Note that I said “stage of career”, not age. A postdoc is a junior researcher. Admiteddly there are some, possibly unrelated to their training, professions that they could have access to (like in the finance sector) in which they might get paid more. Having said that, if childcare becomes a problem in academia, a profession in finance is truly incompatible with children.

The author nonetheless believes that the reason for postdocs leaving is the low salaries. However, only very few of those postdocs will ever have a chance to make it to a tenure track, so leaving the profession whilst being a postdoc will be a reality sooner or later. Still she does think that this affects women more than men. The question is: does this really affect them at this stage because of what they are living at that particular moment or because of the prospect of what is going to come if they were to continue advancing in the academic ladder? The author believes the former. I believe it is actually the latter. Unlike what she tries to convey, things only get harder for women. At the end of the day, a postdoc does not have the final responsability for a multimillion project failing; or to manage a team or researchers; or to meet deadlines established by funding bodies and involving teams from all around the world which are not going to shift in time just because your two year old got chickenpox and he can not attend nursery; or to correct PhD thesis that need to be submitted by a certain date; ah! and how about having to mark 200 scripts in two days, which means that you need to get emergency childcare at $30 an hour? These are just some examples of what is going to happen later on if one continues scaling up the ladder. A postdoc can easily go on maternity leave and not look back for months. A female faculty member can not even do that. I still have to meet one of my female colleagues who was able to leave their job behind. I know of people who were marking scripts while still being in the hospital after giving birth, and all of us were attending meetings on weekly basis.

So, really, does the author think postdocs have it difficult and things relax when a woman gets higher? And tenure track and what comes later with children are easy rides?

I completely agree with her in the fact that salaries should be higher, but I am not sure this increase should be at the postdoc level. AT the end of the day it is a low responsability junior job. If a woman believes that a postdoc role is incompatible with the way she wants to raise children, then the decision of leaving is probably the right one, because it is only going to get harder.

I was in the tenure track in my twenties, got my permanent position at 31, was an associate professor at 34 and I am close to get the full professorship still in my 30s. I have two children under five. Three quarters of my net salary is spent on childcare, part of the reason being that with the level of responsability of a faculty position, basic childcare is not enough, and backup cover is necessary. Academia is just not easy, and there should be much more child support, but I don’t really believe this is the reason why female postdocs leave.

The analysis focuses on the postdoc stage because that is when the transition to women being underrepresented happens. The numbers show that most women leave just before or as postdocs, not once they obtain a tenure-track job.

The “professional characteristics” of the author are completely immaterial to the argument (incidentally, you are not even correct in your assumption that I am a postdoc). Do you disagree with analysis of the financial crisis by anyone who was not head of a large bank? One does not need to have been a mouse to analyze the behavior of mice, for example. The same points I made could be made by someone who is (gasp) not even a scientist.

The argument is not based on personal experience but rather the economics of career alternatives and the little data that exist about women’s choices within the scientific career trajectory (see the citations in the original post).

“Imagine that we paid postdocs, say, $75,000/year. This is a modest increase from current rates…” From the $45,000 that is even padded, this would be a 66% increase–definitely not “modest” and from the actual current entry around $39,000 it is about a 92% increase.

$45,000 is not padded in many places and available fellowships offer more than that.

An increase to $75,000 is completely modest *in comparison to the alternative career choices available.* I could have called for matching postdoc salaries to junior law associates, banking analysts, or management consultants but recognize that that would be way above PI salaries and, while those are alternative career options for many postdocs, an average across all alternative careers is probably more appropriate.

Post-docs do not have the option of those other careers unless they get other training, especially law. The list given does not seem similar enough to compare. Why not compare to medical residents who make about the same amount and are seen as finished with a doctoral degree but still in training for a full, independent career?

The basis for the argument does not seem to say that Post-docs are worth more money, just that if they made more, more women might stay. While I agree that the money is one deterrent, the logic behind many of these comments falls short. It would be like going to your boss and saying you need a raise because you just bought a new house, your car died, etc, instead of going based on merit, skill, and accomplishment. At least, that is what it seems many are saying.

Andrea:

There’s a HUGE difference between a medical residents vs POSTDOCS… at the end of the residency, a position is guaranteed, unless you screw up royally. At the end of a postdoc, is most likely another postdoc, with no way out. These days old postdocs have problem even staying in science. The longer you are a postdoc, the harder it is to get out.

But what does that have to do with the argument? If anything, a further point that you shouldn’t even compare it to law and business.

“It would be like going to your boss and saying you need a raise because you just bought a new house, your car died, etc, instead of going based on merit, skill, and accomplishment.”

Completely agree Andrea. I wanted to high five the screen. I can’t even imagine telling my CEO that, even though I chose this field and knew what the pay was, I should make more money because it is too hard to get another job. I should also have a raise because I chose to buy a house and have kids (even though my salary makes these choices difficult to manage).

In my opinion, your career is about choices. If you want to get a PhD, you should recognize that you won’t get paid very much as a grad student or a post doc and that it will take time and dedication (and if you aren’t get a science PhD, an ungodly amount of student loans). If you want to go into academia, you should know it takes amazing papers, grant funding, and probably a few people dying for you to get a faculty position. If you want to have kids, you probably know it takes time and money and that it will be hard to juggle career and kids. But these are all choices. Unless someone is literally forcing you to get a PhD, have children, and do a 7 year post doc. But those types of situations only happens in Lifetime movies with colons in the title. If that is happening to you, pm me and sally field and I will come rescue you.

I am not saying you can’t have it all (a PhD, a faculty position, and children), but you may not get it at the time you want it in and at the pay you want. If you want to make 120K like a lawyer, go be a lawyer (though they didn’t get paid to go to postgrad school like we did). If you want to have kids and be able to afford childcare, then wait until you have job where you can afford childcare. Choices…Wants…insert line about cake and wanting to eat it. We all know these things when we start down the road and yet still people complain when it goes exactly as everyone told us it would be.

Again, I agree it should be more money as it should account for increases in cost of living. But a transitory, educational position like a post doc getting paid $75K with childcare and no obligations of getting tenure….psh…why would you ever leave? Add on two weeks of vacation, dental and vision, and a moderately aggressive 401K plan and even I would consider going back!

We need both!!!, graduate students and postdocs are the life of a scientific laboratory, and both should be paid more. A computer science major with a bachelor’s degree earns $90,000, a newly graduated law student earns up to $120,000, …We are paying our graduate students (22-30 years old) only $15,000-$20,000, and post docs (27-35) an meager $30,000 – $55,000?…. Not reasonable at all. We need to get the ball rolling for change, both at the Institutional level as well as establish a dialog with the funding sources….But more importantly, the students and postdocs should be in the forefront of the discussion…

Thanks, Martha! Totally agree. Hoping all this discussion at least gets the ball rolling a little…

But what does that have to do with the argument? If anything, a further point that you shouldn’t even compare it to law and business.

This was supposed to post on an earlier comment.

“Post-docs do not have the option of those other careers unless they get other training, especially law. The list given does not seem similar enough to compare. Why not compare to medical residents who make about the same amount and are seen as finished with a doctoral degree but still in training for a full, independent career?”

Andrea, you were the one that said why not compare postdoc to MDs that make about the same income (for those few years) And my point was to say these 2 professions are drastically different in career outcome and therefore can not be compared as you did.